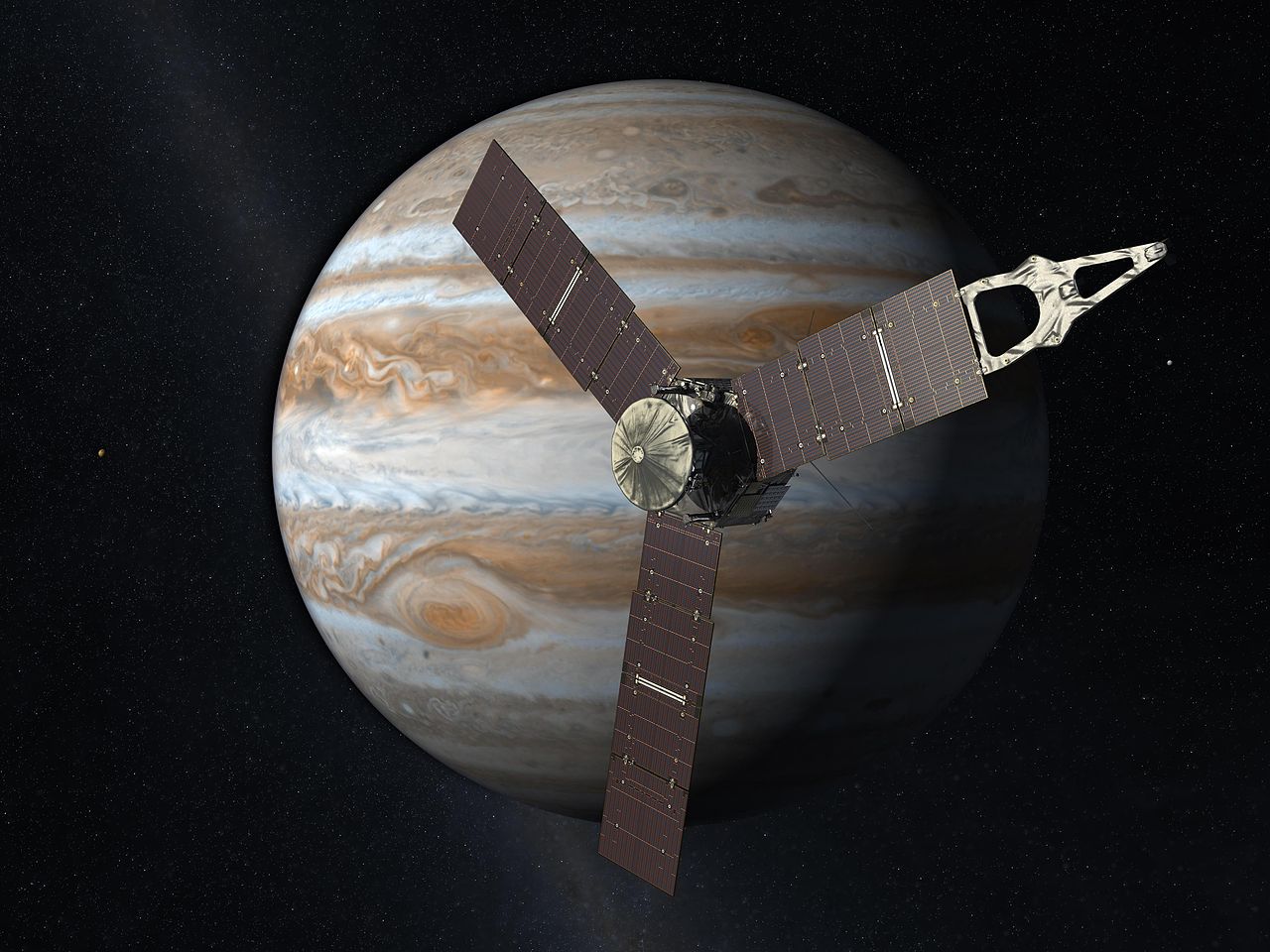

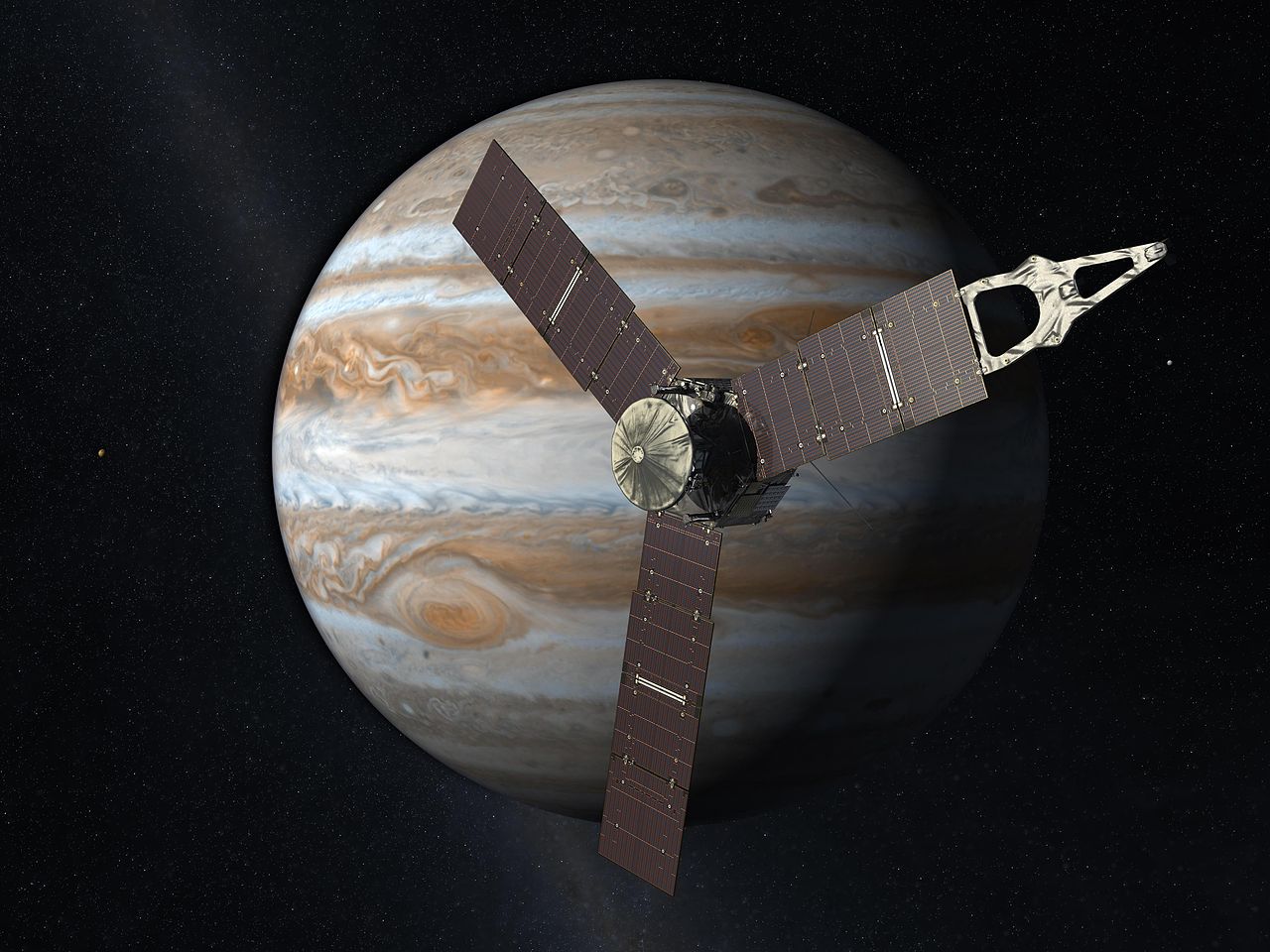

Juno is a NASA space probe orbiting the planet Jupiter. It was built by Lockheed Martin and is operated by NASA‘s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The spacecraft was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on August 5, 2011 (UTC), as part of the New Frontiers program, and entered a polar orbit of Jupiter on July 5, 2016 (UTC), (July 4, US time) to begin a scientific investigation of the planet. After completing its mission, Juno will be intentionally deorbited into Jupiter’s atmosphere.

Juno‘s mission is to measure Jupiter’s composition, gravity field, magnetic field, and polar magnetosphere. It will also search for clues about how the planet formed, including whether it has a rocky core, the amount of water present within the deep atmosphere, mass distribution, and its deep winds, which can reach speeds up to 618 kilometers per hour (384 mph).

Juno is the second spacecraft to orbit Jupiter, after the nuclear powered Galileo orbiter, which orbited from 1995 to 2003. Unlike all earlier spacecraft sent to the outer planets, Juno is powered by solar arrays, commonly used by satellites orbiting Earth and working in the inner Solar System, whereas radioisotope thermoelectric generators are commonly used for missions to the outer Solar System and beyond. For Juno, however, the three largest solar array wings ever deployed on a planetary probe play an integral role in stabilizing the spacecraft as well as generating power.

Juno was selected on June 9th 2005 as the next New Frontiers mission after New Horizons. The desire for a Jupiter probe was strong in the years prior to this, but there had not been any approved missions. The Discovery Program had passed over the somewhat similar but more limited Interior Structure and Internal Dynamical Evolution of Jupiter (INSIDE Jupiter) proposal, and the turn-of-the-century era Europa Orbiter was cancelled in 2002. The flagship-level Europa Jupiter System Mission was in the works in the early 2000s, but funding issues resulted in it evolving into ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer.

Juno completed a five-year cruise to Jupiter, arriving on July 5, 2016. The spacecraft traveled a total distance of roughly 2.8 billion kilometers (18.7 astronomical units; 1.74 billion miles) to reach Jupiter. The spacecraft was designed to orbit Jupiter 37 times over the course of its mission. This was originally planned to take 20 months. Juno‘s trajectory used a gravity assist speed boost from Earth, accomplished by an Earth flyby in October 2013, two years after its launch on August 5, 2011. The spacecraft performed an orbit insertion burn to slow it enough to allow capture. It was expected to make three 53-day orbits before performing another burn on December 11, 2016 that would bring it into a 14-day polar orbit called the Science Orbit. Because of a suspected problem in Juno‘s main engine, the burn of December 11 was canceled, and Juno will remain in its 53-day orbit for its remaining orbits of Jupiter.

During the science mission, infrared and microwave instruments will measure the thermal radiation emanating from deep within Jupiter’s atmosphere. These observations will complement previous studies of its composition by assessing the abundance and distribution of water, and therefore oxygen. This data will provide insight into Jupiter’s origins. Juno will also investigate the convection that drives natural circulation patterns in Jupiter’s atmosphere. Other instruments aboard Juno will gather data about its gravitational field and polar magnetosphere. The Juno mission was planned to conclude in February 2018, after completing 37 orbits of Jupiter. The probe was then intended to be de-orbited and burn up in Jupiter’s outer atmosphere, to avoid any possibility of impact and biological contamination of one of its moons.

Flight trajectory

Launch

Juno was launched atop the Atlas V at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. The Atlas V (AV-029) used a Russian-built RD-180 main engine, powered by kerosene and liquid oxygen. At ignition it underwent checkout 3.8 seconds prior to the ignition of five strap-on solid rocket boosters (SRBs). Following the SRB burnout, about 93 seconds into the flight, two of the spent boosters fell away from the vehicle, followed 1.5 seconds later by the remaining three. When heating levels had dropped below predetermined limits, the payload fairing that protected Juno during launch and transit through the thickest part of the atmosphere separated, about 3 minutes 24 seconds into the flight. The Atlas V main engine cut off 4 minutes 26 seconds after liftoff. Sixteen seconds later, the Centaur second stage ignited, and it burned for about 6 minutes, putting the satellite into an initial parking orbit. The vehicle coasted for about 30 minutes, and then the Centaur was reignited for a second firing of 9 minutes, placing the spacecraft on an Earth escape trajectory in a heliocentric orbit. Prior to separation, the Centaur stage used onboard reaction engines to spin Juno up to 1.4 r.p.m.. About 54 minutes after launch, the spacecraft separated from the Centaur and began to extend its solar panels. Following the full deployment and locking of the solar panels, Juno’s batteries began to recharge. Deployment of the solar panels reduced Juno’s spin rate by two-thirds. The probe is spun to ensure stability during the voyage and so that all instruments on the probe are able to observe Jupiter. The voyage to Jupiter took five years, and included an orbital manoeuvre in 2012 and a flyby of the Earth on October 10, 2013. When it reached the Jovian system, Juno had traveled approximately 19 AU, almost two billion miles.

Flyby of the Earth

After traveling for about a year in an elliptical heliocentric orbit, Juno fired its engine in 2012 near aphelion (beyond the orbit of Mars) to change its orbit and return to pass by the Earth in October 2013. It used Earth’s gravity to help slingshot itself toward the Jovian system in a maneuver called a gravity assist. The spacecraft received a boost in speed of more than 3.9 km/s (8,800 mph), and it was set on a course to Jupiter. The flyby was also used as a rehearsal for the Juno science team to test some instruments and practice certain procedures before the arrival at Jupiter.

South America as seen by JunoCam on its October 2013 Earth flyby

Insertion into jovian orbit

Jupiter’s gravity accelerated the approaching spacecraft to around 210,000 km/h (130,000 mph). On July 5, 2016, between 03:18 and 03:53 UTC Earth-received time, an insertion burn lasting 2,102 seconds decelerated Juno by 542 m/s (1,780 ft/s) and changed its trajectory from a hyperbolic flyby to an elliptical, polar orbit with a period of about 53.5 days. The spacecraft successfully entered Jupiter orbit on July 5 at 03:53 UTC.

Animation of Juno‘s trajectory around Jupiter from 1 June 2016 to 31 July 2021

Orbit and environment

Juno’s highly elliptical initial polar orbit takes it within 4,200 kilometers (2,600 mi) of the planet and out to 8.1 million km (5.0 million mi), far beyond Callisto’s orbit. An eccentricity-reducing burn, called the Period Reduction Maneuver, was planned that would drop the probe into a much shorter 14 day science orbit. Originally, Juno was expected to complete 37 orbits over 20 months before the end of its mission. Due to problems with helium valves that are important during main engine burns, mission managers announced on February 17, 2017, that Juno would remain in its original 53-day orbit, since the chance of an engine misfire putting the spacecraft into a bad orbit was too high. Juno will now complete only 12 science orbits before the end of its budgeted mission plan, ending July 2018.

The orbits were carefully planned in order to minimize contact with Jupiter’s dense radiation belts, which can damage spacecraft electronics and solar panels, by exploiting a gap in the radiation envelope near the planet, passing through a region of minimal radiation. The “Juno Radiation Vault”, with 1-centimeter-thick titanium walls, also aids in protecting Juno’s electronics. Despite the intense radiation, JunoCam and the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) are expected to endure at least eight orbits, while the Microwave Radiometer (MWR) should endure at least eleven orbits. Juno will receive much lower levels of radiation in its polar orbit than the Galileo orbiter received in its equatorial orbit. Galileo’s subsystems were damaged by radiation during its mission, including an LED in its data recording system. Orbital operations The spacecraft completed its first flyby of Jupiter (perijove 1) on August 27, 2016, and captured the first images of the planet’s north pole. On October 14, 2016, days prior to perijove 2 and the planned Period Reduction Maneuver, telemetry showed that some of Juno’s helium valves were not opening properly. On October 18, 2016, some 13 hours before its second close approach to Jupiter, Juno entered into safe mode, an operational mode engaged when its onboard computer encounters unexpected conditions. The spacecraft powered down all non-critical systems and reoriented itself to face the Sun to gather the most power. Due to this, no science operations were conducted during perijove 2. On December 11, 2016, the spacecraft completed perijove 3, with all but one instrument operating and returning data. One instrument, JIRAM, was off pending a flight software update. Perijove 4 occurred on February 2, with all instruments operating. Perijove 5 occurred on March 27, 2017. Perijove 6 took place on May 19, 2017. Although the mission’s lifetime is inherently limited by radiation exposure, almost all of this dose was planned to be acquired during the perijoves. As of 2017, the 53.4 day orbit was planned to be maintained through July 2018 for a total of twelve science-gathering perijoves. At the end of this prime mission, the project was planned to go through a science review process by NASA’s Planetary Science Division to determine if it will receive funding for an extended mission. In June 2018, NASA extended the mission operations plan to July 2021. When Juno reaches the end of the mission, it will perform a controlled deorbit and disintegrate into Jupiter’s atmosphere. During the mission, the spacecraft will be exposed to high levels of radiation from Jupiter’s magnetosphere, which may cause future failure of certain instruments and risk collision with Jupiter’s moons.

Jupiter imaged using the VISIR instrument on the VLT. These observations will inform the work to be undertaken by Juno.

Planned deorbit and disintegration

NASA plans to eventually deorbit the spacecraft into the atmosphere of Jupiter after 2021. The controlled deorbit is intended to eliminate space debris and risks of contamination in accordance with NASA’s Planetary Protection Guidelines.

Team

Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas is the principal investigator and is responsible for all aspects of the mission. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California manages the mission and the Lockheed Martin Corporation was responsible for the spacecraft development and construction. The mission is being carried out with the participation of several institutional partners. Coinvestigators include Toby Owen of the University of Hawaii, Andrew Ingersoll of California Institute of Technology, Frances Bagenal of the University of Colorado at Boulder, and Candy Hansen of the Planetary Science Institute. Jack Connerney of the Goddard Space Flight Center served as instrument lead.

Cost

Juno was originally proposed at a cost of approximately US$700 million (fiscal year 2003) for a launch in June 2009. NASA budgetary restrictions resulted in postponement until August 2011, and a launch on board an Atlas V rocket in the 551 configuration. As of June 2011, the mission was projected to cost US$1.1 billion over its life.

Scientific objectives

The Juno spacecraft’s suite of science instruments will:

- Determine the ratio of oxygen to hydrogen, effectively measuring the abundance of water in Jupiter, which will help distinguish among prevailing theories linking Jupiter’s formation to the Solar System.

- Obtain a better estimate of Jupiter’s core mass, which will also help distinguish among prevailing theories linking Jupiter’s formation to the Solar System.

- Precisely map Jupiter’s gravitational field to assess the distribution of mass in Jupiter’s interior, including properties of its structure and dynamics.

- Precisely map Jupiter’s magnetic field to assess the origin and structure of the field and how deep in Jupiter the magnetic field is created. This experiment will also help scientists understand the fundamental physics of dynamo theory.

- Map the variation in atmospheric composition, temperature, structure, cloud opacity and dynamics to pressures far greater than 100 bars (10 MPa; 1,450 psi) at all latitudes.

- Characterize and explore the three-dimensional structure of Jupiter’s polar magnetosphere and auroras.

- Measure the orbital frame-dragging, known also as Lense–Thirring precession caused by the angular momentum of Jupiter, and possibly a new test of general relativity effects connected with the Jovian rotation.

Among early results, Juno gathered information about Jovian lightning that revised earlier theories.

Read the full article on Wikipedia

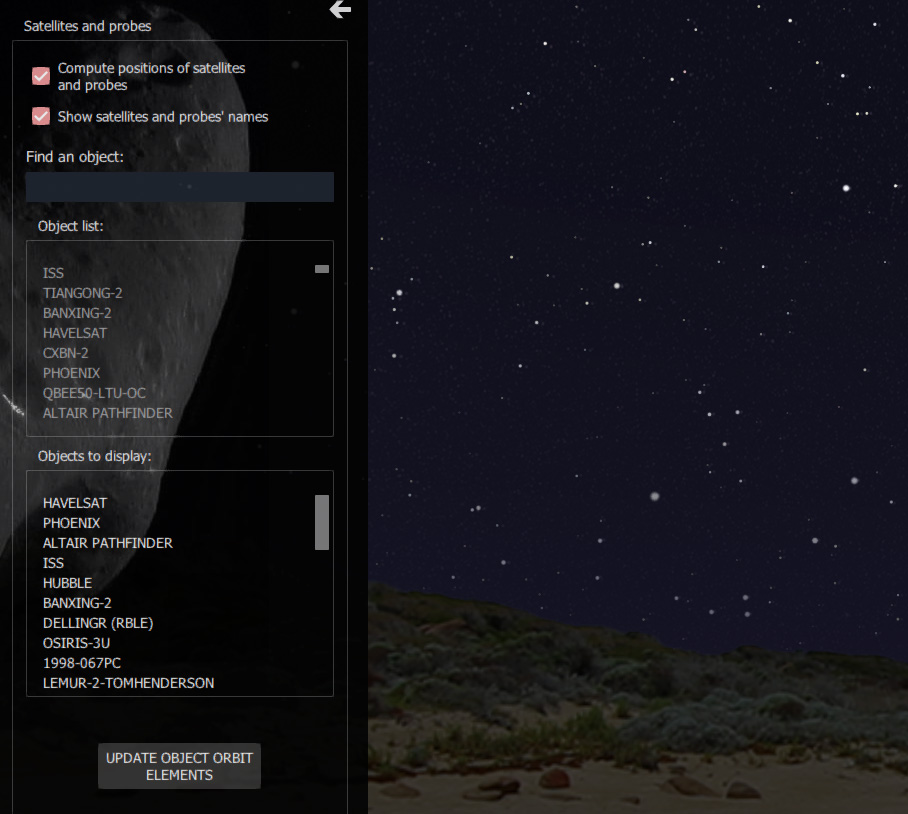

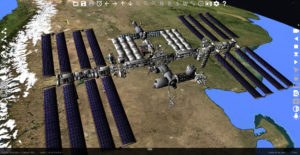

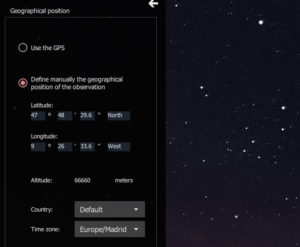

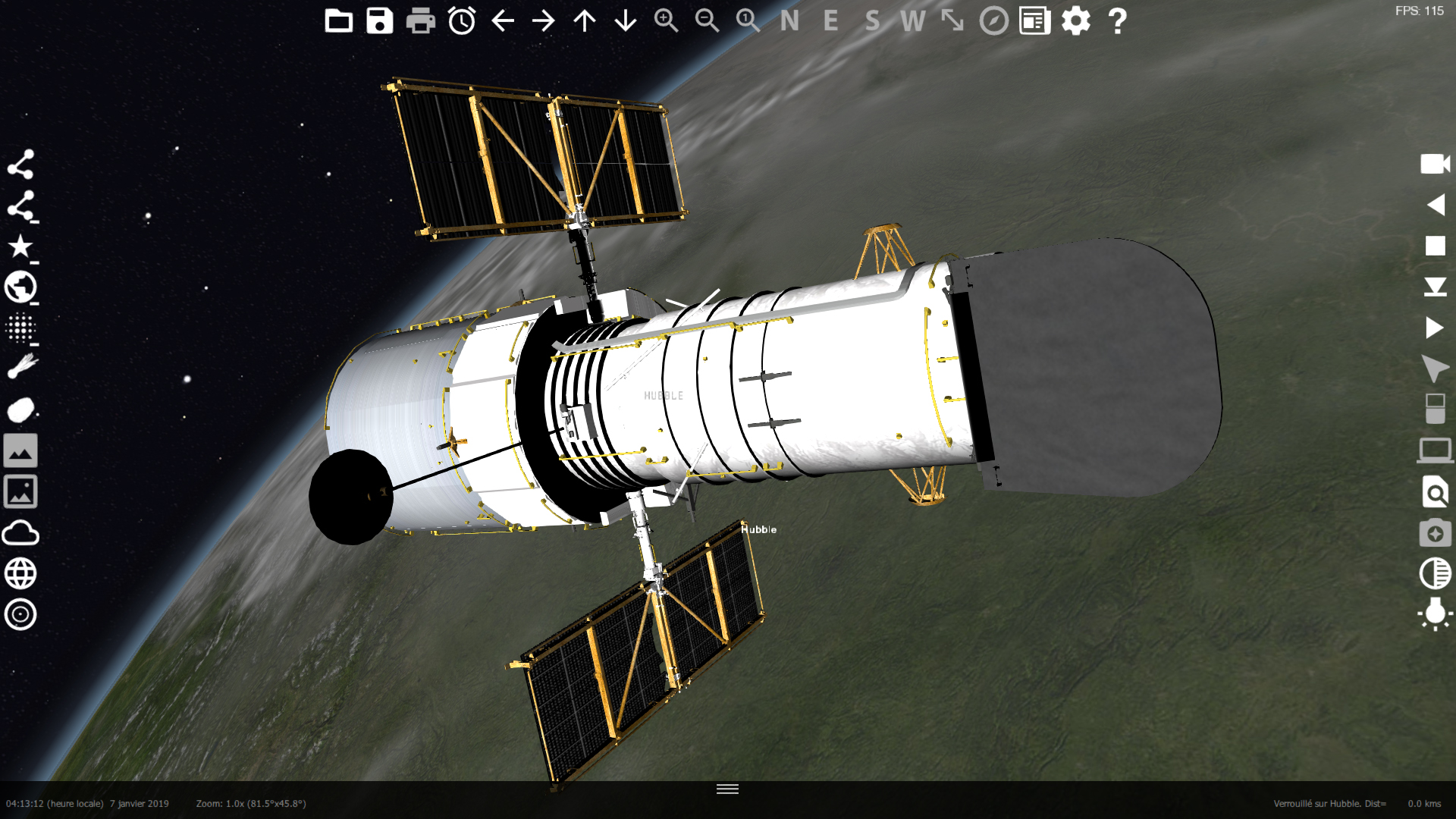

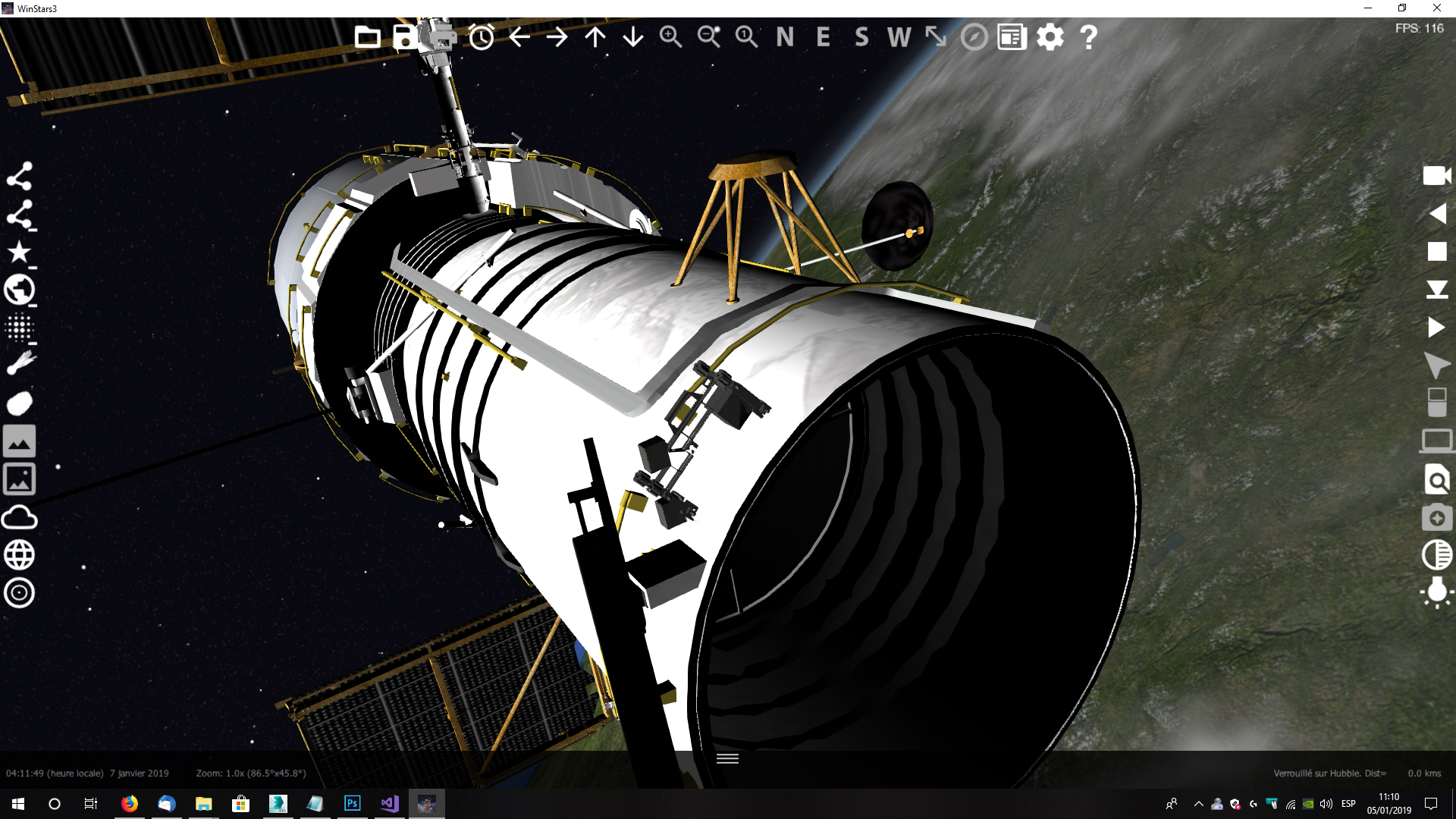

If you want to view the Juno mission in WinStars, please download the latest version of the program (3.0.56) and activate the Juno module .